People are often curious what it means to be bilingual or multilingual, and who qualifies as bilingual. One might expect researchers in the field to have a strict definition of bilingualism. But the truth is that I (and others in my field) have a pretty open definition of what “counts” as bilingual. I would say that a bilingual (or multilingual) is someone who has learned or uses two (or more) languages to some degree during their life. It’s estimated that bilingualism is the global norm—that there are more bilinguals and multilinguals compared to monolinguals.

But don’t you need to be perfectly proficient or balanced in your languages to qualify as bilingual?

There is this idea of a “perfect” form of bilingualism, where someone could function like a “pristine” monolingual speaker in each of their languages. I use scare quotes here because these ideas are part of a mythology surrounding bilingualism and comparisons to monolinguals.

Learning to speak a second language changes the game altogether, making it difficult or impossible to draw comparisons between bilinguals and monolinguals. Most notably, people who become highly proficient in a second language experience a phenomenon known as cross-language activation, where information from both languages becomes activated even when they are trying to use one language alone. It’s thought that cross-language activation occurs all the time for many different aspects of language processing. Sometimes cross-language activation can facilitate communication, and other times it can impede it. Importantly, cross-language activation can occur even in a bilingual’s most proficient language (often, but not always, the language they acquired at birth). Thus, a bilingual language systems exhibit a type of interactivity that does not occur (to the same extent) in monolingual language systems.

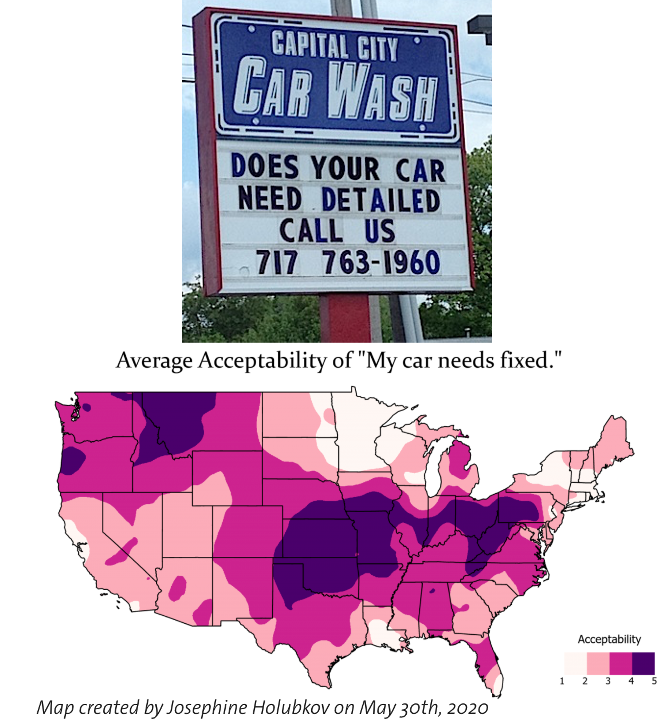

Next, monolinguals aren’t perfect: they exhibit individual variability in language abilities, including spoken fluency, spoken comprehension, writing ability, and reading ability. People (not just monolinguals) also differ in terms of which varieties of a language they speak. For example, to an English speaker who grew up in parts of Pennsylvania “the car needs fixed” sounds just fine. However, to speakers from other parts of the country, this utterance sounds terrible (the car needs to be fixed!!!). This means that even people who grew up speaking the same language disagree on how it should be spoken!

Image adapted from the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project.

Image adapted from the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project.

Lastly, language proficiency is a not a one-dimensional construct that simply increases with practice. Language proficiency is context dependent, and people acquire proficiency in languages for different reasons. Someone can become a very proficient reader in a language without the ability to speak it fluently. Someone who acquires French from birth in the home and English at school might be more proficient in French when it comes to speaking about household items. However, this individual might be more proficient in English when it comes to talking about concepts learned outside the home such as biology or technology.

In sum, being bilingual or multilingual is a matter of degree and becoming bilingual will depend on the individual and their situation. For more on this topic, check out the additional resources, below.

Further reading

Juggling two languages in one mind by Judith Kroll

What a Bilingual’s Languages are Used For by François Grosjean

6 Potential Brain Benefits of Bilingual Education on NPR featuring several bilingualism researchers